Methane emissions are increasingly becoming a focus for international climate policy. Pressure to cut them will continue to grow

“A small leak will sink a great ship” was a favourite saying of Benjamin Franklin, the writer, scientist, diplomat and Founder Father of the US. It could also be a pretty good slogan for the struggle to prevent catastrophic climate change. Methane emissions from leaks, venting and other sources have increasingly come into focus in policy discussions and among businesses as an important contributor to global warming.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s 6th Assessment Report, published in August, highlighted methane as the second most significant greenhouse gas after carbon dioxide. Methane emissions alone are estimated to have caused about 0.5 °C of global warming since the 19th century, about two-thirds as much as carbon dioxide.

Texas Oil & Gas Facilities

The growth in global methane emissions since 2007 has been largely driven by the fossil fuel industries and agriculture, the IPCC scientists concluded. Roughly 30% of human-created methane emissions come from the fossil fuel industries, with agriculture, waste and biomass accounting for the rest. Within that fossil fuel section, the coal industry is responsible for about one-third, and the oil and gas industry two-thirds.

So although oil and gas production, processing and transport only accounts for a minority of human-created methane emissions, it is still a significant contributor. And whereas solutions in agriculture can be elusive — adding seaweed to cows’ diet to reduce their burps and farts is still being tested — the strategies and techniques for capturing methane and preventing leaks in the oil and gas business are well-established. The UN Environment Programme argued in its new Emissions Gap Report 2021, published this week, that using existing technologies to capture methane leaking from oil, gas and coal facilities could reduce the sector’s emissions by 40-50% by 2030, “much of it at net-zero cost”.

A new international Global Methane Pledge, launched by the US and the EU in September, now has 32 countries signed up, including nine of the world’s top 20 methane emitters. The participating countries have pledged to commit to “a collective goal of reducing global methane emissions by at least 30% from 2020 levels by 2030”. Implementing the pledge would on its own cut global warming by 2050 by 0.2 °C, the US government says.

As part of that global effort, the Biden administration and Democrats in Congress have been pushing for a “methane fee”, to be levied on oil and gas companies through some formula linked to methane emissions. At the time of writing, the future of this proposal is uncertain, as negotiations in Congress continue over the proposed. Build Back Better Act.

The methane fee was included in the first published version of that bill, but had to be scaled back after opposition from Joe Manchin, a centrist Democratic senator from West Virginia, which has significant coal and gas production. The 50-50 Democrat-Republican split in the Senate means the bill would need support from every single Democrat to pass, putting Senator Manchin in a highly influential position. The most recent draft bill circulated on Thursday still included a fee, but with a phase-in over three years and other years modifications to cushion its impact. There are also carrots as well as sticks: $775 million for the Environment Protection Agency to provide “grants, rebates, contracts, loans, and other activities” to help companies cut methane and other emissions.

The US oil and gas industry had objected strongly to the plan, arguing that it would “levy an unreasonable, punitive fee on methane emissions only from oil and natural gas facilities that could jeopardize affordable and reliable energy with likely little reduction in greenhouse gas emissions.” The latest revision of the plan addresses a key issue in earlier versions: that oil-focused producers were likely to be hit much harder than their gas-focused peers. But analysis of company disclosures and of methane data in Wood Mackenzie’s Emissions Benchmarking Tool, suggests that the proposed fee could still have had widely varying impacts across companies and across basins.

For example, production in the Northeast of the US, mostly gas from the Marcellus and Utica shales, last year had an average methane emissions intensity of 3.8 tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent per thousand barrels of oil equivalent produced, whereas the Mid-Continent region had an emissions intensity almost four times greater at 14.75 tCO2e/kboe.

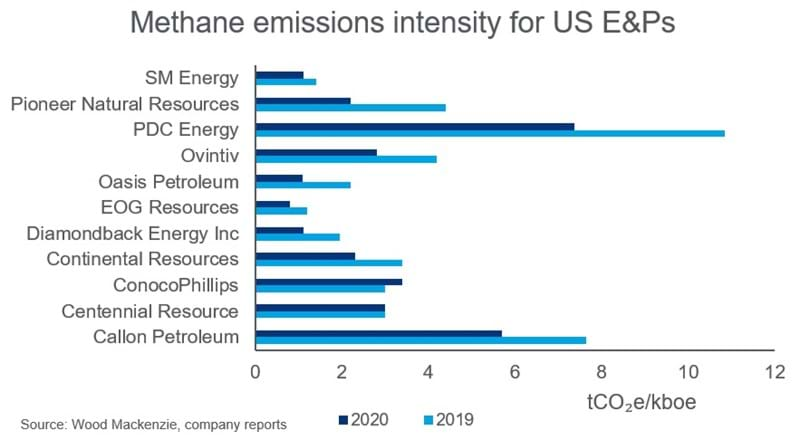

There is a similarly wide variation between companies, as you can see in this sample of reported methane emissions intensities of production from some of the larger US E&Ps. Many have set goals to reduce emissions, and made progress on those objectives in 2020, with Pioneer Natural.

Resources reporting a particularly steep decline in its methane intensity. But not all companies are moving in the same direction, and their starting points can be very different.

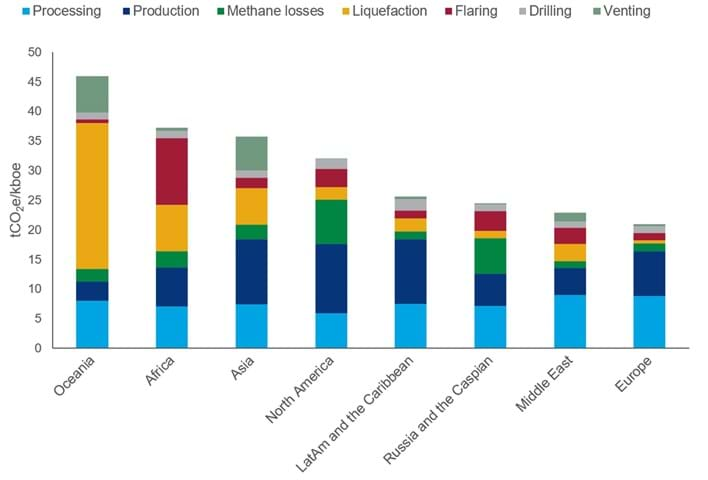

Another chart that is worth looking at in this context is this one showing international comparisons, again using the Emissions Benchmarking Tool. North American production is neither the highest nor the lowest for emissions intensity among upstream operations worldwide. But it is striking that the green bar for methane losses is the largest for any region. That points to both a problem for North American producers, and an opportunity for improvement.

Investors and regulators will keep up the pressure on US companies to reduce their methane emissions, even if the fee does not pass into law. The Environmental Protection Agency has been working on new methane regulations, which are expected to be published soon. Michael Regan, head of the agency, said at a conference in August that reducing methane emissions has “never been done as aggressively as we plan to do it.”

The largest companies already have goals that commit them to steep reductions. Chevron has set a target of cutting its methane intensity by 50% from 2016 levels by 2028, to 2 tCO₂e/kboe by 2028. ExxonMobil’s goal is a 40-50% reduction from 2016 levels by 2025. This week ExxonMobil said it supported the Global Methane Pledge, and was committed to working with the US government, the European Commission and other governments to help achieve its objectives.

Anuj Goyal, a senior analyst in corporate research at Wood Mackenzie, says that smaller US operators just starting to address emissions, methane is “the lowest-hanging fruit with the shortest payback period”. Independent third-party certification could help those companies convince sceptical investors that they are making genuine progress towards emissions goals.

If the proposed fee system is ultimately rejected, the decline in emissions across the industry will be slower. But methane will remain a big issue for the industry in the US and beyond.

Energy News